Word Hunters: Johanna Hedva In Conversation with Gabrielle Welsh

I first encounter the work of Johanna Hedva far away from home and with staggering force: I turn the corner of an exhibition wall, startled by the experience due to my own recent retreat from ‘contemporary art,’ and a Text-to-Speech voice reads from a pink-screen, “Yow now listen Motherfuck if not nihilism what?”

These are the opening lines to Hedva’s 2018 novel, On Hell, published by Sator Press, a whirlwind of interviews and run-ons with ex-con Rafael Luis Estrada Requena, conducted by the journalist, Motherfuck. Rafael is trying to fly, or rather, he is going to fly, and the interviews follow the process of bodily transformation as arms become wings, human becomes flight. He speaks against the prison industrialist complex and capitalist-flows that have broken him, his words running-on as ramblings dotted with insurrectionary ideas; he is a body deeply shocked by the state and begin-ning anew, but not fresh. In his recent release from prison, he is approached by Motherfuck, to whom he cautiously confesses: “I lost all the friends I had on and obviously obviously lost my convictions my resistance my quote unquote insurrectionary tendencies my fuck my father fuck all everything but losing the taste for choco-late I don’t know that did probably bigger damage in the way that’ll crush a bitch.” He still agrees to sit for several interviews. Ultimately, On Hell exemplifies that words are tools of power, pointing to histories (at least within the states)

of speech and repression with a gleaming facade of freedom, “free speech.” As Rafael says, tripping over his own words, “The government they’re poets. They’re word hunters.”

GABRIELLE WELSH: I haven’t really read any book like this before, mostly the structure—for lack of a better explanation—the rambling from Rafeal that picks up pace indefinitely and the rule-break-ing feel of it all. It’s the speediest 107 pages! Were you looking to any specific writers or pieces? Or influences outside of “art?”

JOHANNA HEDVA: Thank you for saying that. The biggest compliment I’ve gotten about this book is that it’s a quick read. I feel very proud of that, because it really shouldn’t be. The language is dense and knotted and the sentences are very long, and it took me a hundred drafts (not exaggerating)to get the language right, to be not only readable but surging and alive and something that floods into your head really fast.

Early on I made the decision not to use commas. Commas are a gesture of trust that the writer extends to their reader. They’re like a little check-in, where the writer pauses and reaches out their hand and says, “Hey, are you cool to keep going with this sentence? Are you with me? We can pause for a moment so you can catch up. You good now? Okay, let’s keep going.” I didn’t want that. I wanted my reader to feel like they were being taken to the end of the sentence, whether they wanted to go there or not. Like being in a truck with no brakes, barreling down a hill.

For influences, my Gemini north node means that I have a wild constellation of random and disparate things swirling around me at all times. Kathy Acker’s Empire of the Senseless is the most obvious influence, not just for the language but also the drawings. Cyberpunk movies from the 1990s—I’m a huge fan. I could spend this whole interview talking about Johnny Mnemonic and Tetsuo and Hackers and The Matrix.

I’m also really into noise, and I wanted the overall effect of the book to be like seeing a really mythical live noise show, like Prurient or Merzbow, both of whom I love. Just like a huge, heavy blast that doesn’t relent but is swarming with nuance and shakes your whole body into the void.

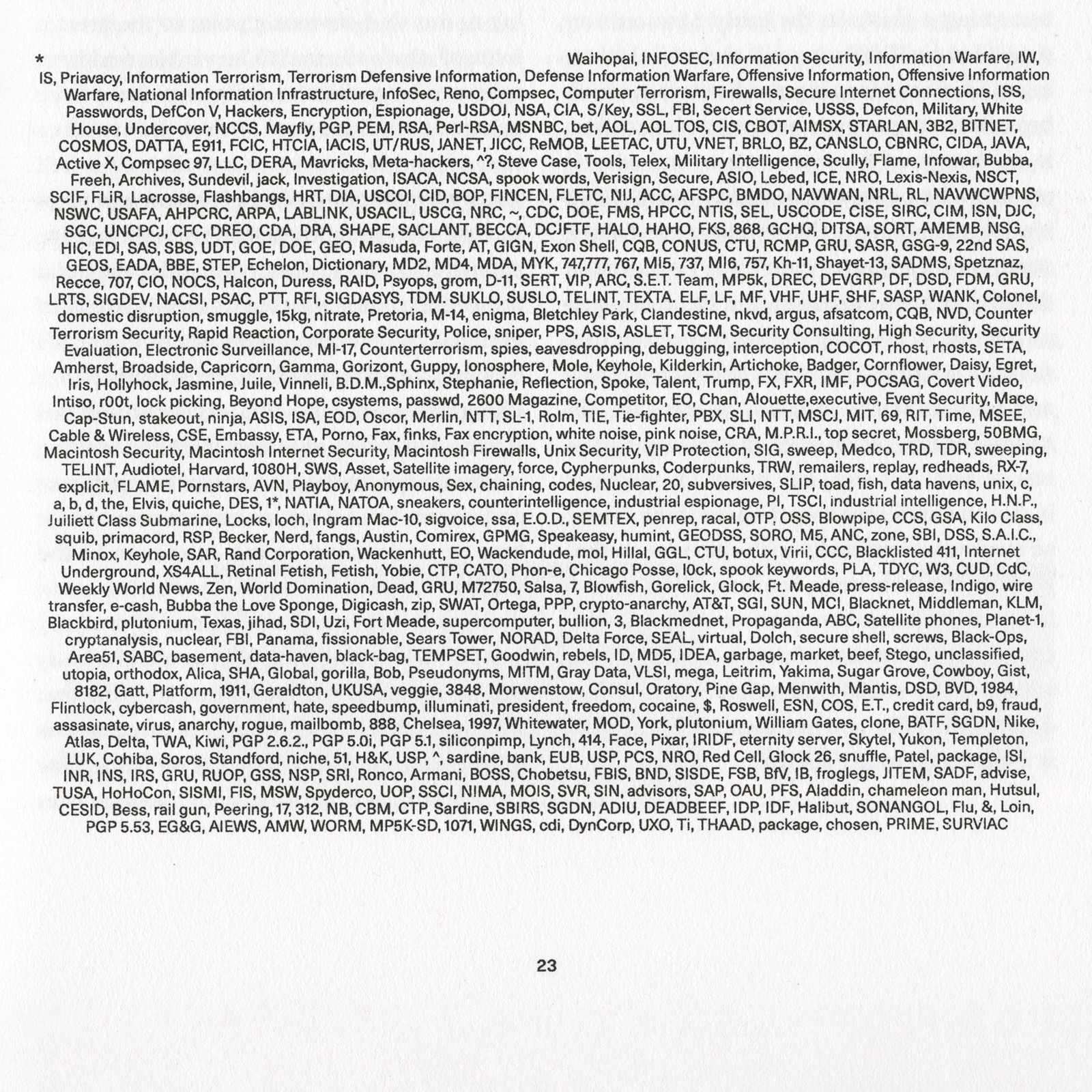

More than anything, though, were the documents surrounding Anonymous and “hacktiv-ism” in the 2000s. I read a lot of blog posts and threads from listservs about cyber secu-rity and “cypherpunks” and how to “hack the world” and shit like that. It felt very insurrec-tionary, those early years in the 21st century when activism collided with hacking, and I admit I have a nostalgia for it. My favorite was LulzSec. I was so taken with the language in their leaked chatroom logs, these streams of punctuation-less lines that were explod-ing with weird witticisms and the raunchy, giddy viscerality that only teenage boys can summon. Rafael is sort of based on Topiary, one of the members of LulzSec who was their “spokesman.” The way he writes and talks is just brilliant, and also very fast and whirli-gig-y. I started writing the book when the list of words the NSA flags in emails* was leaked, sometime in the summer of 2013. That list of words went around, and I was riveted by the fact the government spends a bazillion dollars to surveil people using words like “beef” and “package” in their emails. Returning to that list for its poetry was helpful throughout the writing process.

GW: The two characters of your novel—Rafael and Motherfuck—have this professional yet friendly relationship, where there are bits of trust and intimacy, yet the two are always on the outskirts of each other’s lives, with Motherfuck inserting herself, right? Can you speak a little to their rela-tionship, or how you were using Motherfuck as an interviewer, or someone prodding?

JH: It’s the literary device of the prison confessional. For narrative purposes, I needed a reason for Rafael to talk, and specifically, to talk out loud to someone, about who he is, and what he’s done, and why. I wanted his voice to be spoken—even performed—for the reader to be able to hear him.

Motherfuck is a journalist, and she’s working at the time when “citizen journalism” was becoming a thing in the early 21st century, propelled by Wikileaks and the whistleblowing of Chelsea Manning and Snowden, which brought into question both what journalism is, in the age of the internet 2.0, and what it means to be a citizen in a digital world. (And it’s not a coincidence that this happened at the same time as “hacktivism” was becoming a thing.) I’m not a journalist, but I’m really curi-ous about it, because the nature of the rela-tionship between journalists and their sources and subjects seems so messy to me. Like, on a social or emotional level, the relationship is one of care, but also, not really. Or maybe it is, but in a different way than we think. To be so involved emotionally with someone so that you can tell their story, but how this is always irrevocably bound to your own story—the complicated sociality of that is a puzzle. Like, what are the social obligations there? What does a journalist owe her source? Even, what is a journalist to her source?

GW: Now that you say that, I’m thinking back, Motherfuck isn’t rewriting or editing, right? It’s Rafael’s story in his own words, without the end piece published in the paper. Rather, you’re presenting us with her notes and transcriptions.

JH: Yes, exactly. This is because Motherfuck does extend a kind of care to Rafael: She keeps his words intact, because he asks her to. He says to her, “do me right, do me real.” So she does by quoting him at length, rather than paraphrasing, or doing any kind of editing.

Of course, though, in the end, it is her story, not his, being told, because she is the one fram-ing it. So the question of who a story “belongs” to is there. These discussions at the moment, in the worlds of movies and literature, of “who is allowed” to tell whose stories are interest-ing to me, and obviously point to the greater issue of who’s allowed to be visible, and have agency about their visibility, in the public sphere at all. But I tend to find the conversa-tion of who is allowed or not allowed to tell a story frustrating because it often replicates the law of ownership, and I generally want to abolish all forms of ownership. Like, the point is that everyone is affected by these systems of oppression, that no one gets free of it, and it’s this invasion that needs to be accounted for. Experiences are embodied, certainly, and this is very important in terms of understanding whose bodies and voices are given platforms and power, but I think we have to account for how we understand certain stories to be the territory of certain people, by which I mean, we have to explode the very idea of territory, or of bodies, being own-able at all. If a body can be owned it can be owned by someone who is not in it, so the concept of ownership is not helping us. Also, it’s like, if we demarcate our territory of experience with the same laws we use to enforce private property, we start to talk about forms of embodiment in terms of wealth, or poverty. And, anyway, I just find there to be way more enmeshment, in terms of identity and subjectivity, than we are probably comfortable with, and this is what fiction, if nothing else, is about exploring.

GW: I first ‘read’ bits of On Hell in an exhibition space, at the iCa in London. Did you have any intention for your written work to move from the page to the quote-un-quote white wall? Into this text-to-speech attention-grabbing robotic film?

JH: Yes, definitely, and from the beginning. The best way I can explain why is that, for me, the definition of writing is that it’s language embodied. Which means that writing is always more than just words on a page. It’s material, it has a body, even if it’s just screaming in a room or dragging a hand through water.

When I’m writing, I consider the sound and visuality of the language as much as I do the linguistic meaning. I often tape onto my wall pages from whatever text I’m working on, so I can see how it looks, how it exists as an image. I often read it aloud as I write, so I can hear the language being spoken with a voice, and I try to use different voices: whispering, shouting, etc. (Shouting On Hell, by the way, is fun af.) With On Hell, I always printed it on this pink paper, from the first time I printed the first draft. I wanted the page itself to feel like flesh—a little chunk of skinless flesh.

And it’s not really a robotic film. The voice in the video is a speech-to-text software that is used for disability access, so it’s very familiar to the people who use it regularly. I made the video, slide by slide, by hand in InDesign, the spatiality of the text was wedded to its mean-ing. My undergrad is in design, and so the font and color and layout of both the book and the video are extremely important. Their mate-riality is as meaningful as any other element.

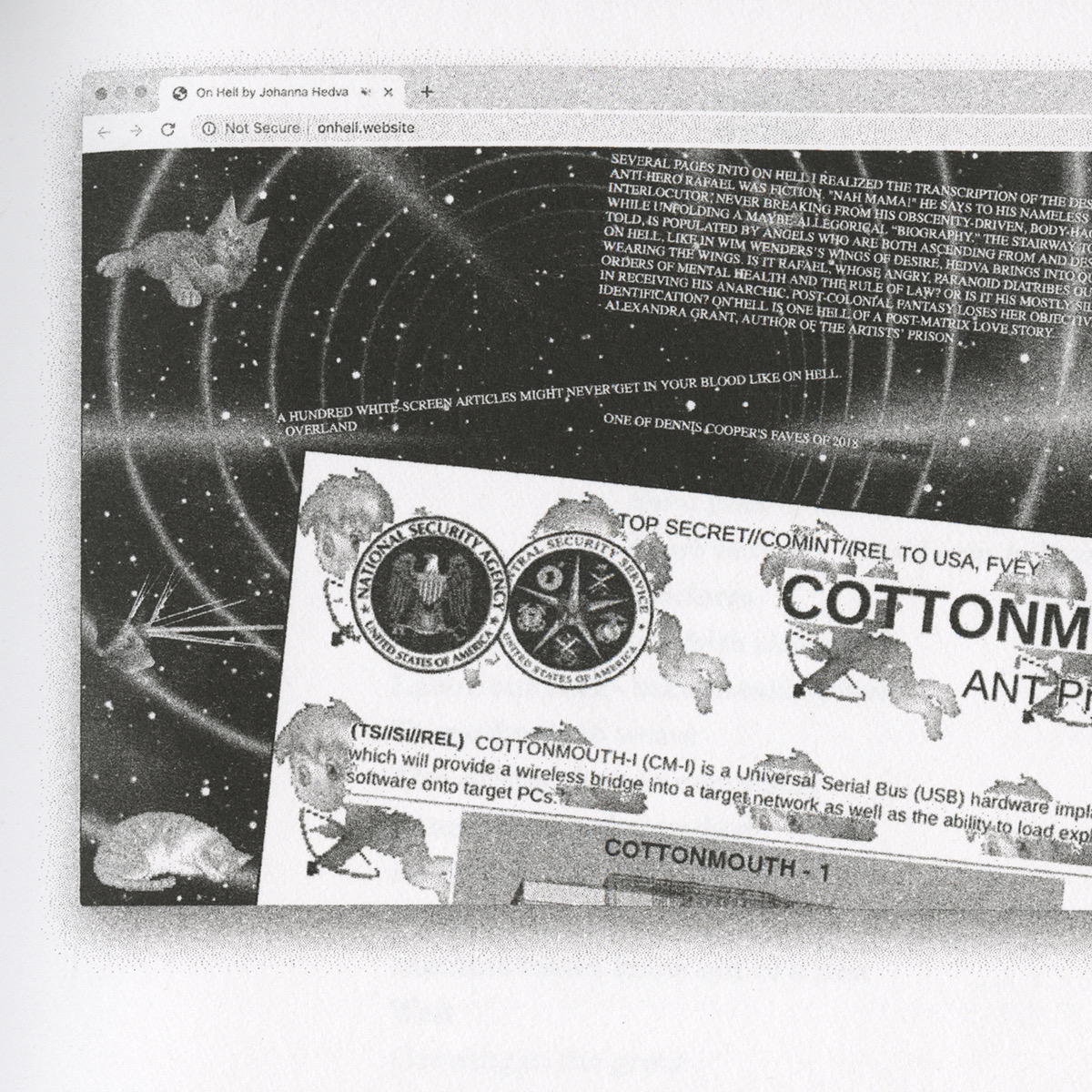

I must take a moment to recognize my publisher, Ken Baumann of Sator Press, because he supported all of what I wanted for the book, in terms of these “extra-textual” things I’m talking about. It wasn’t just the text he would publish, but I was like, “It has to be printed on this particular shade of pink paper, here’s the Pantone swatch. And the font we use has to be designed by a woman and have a relationship to Los Angeles and to digitality. And we have to have a website with many sparkling cat gifs and leaked NSA documents!” I am so so so lucky that Ken’s response to all that was, “cool, let’s do it!” And that he found Sibylle Hagmann’s Cholla font, which she designed when she was a student at Art Center. It’s based on the Cholla cactus, which lives in Joshua Tree, where Motherfuck ends up.

GW: One of my favorite aspects of the book is the accompanying website—I remember showing it to some friends and one immediately said, Can I please borrow this book? It feels like the visual (and state-based) chaos of On Hell. Do they func-tion in conversation, so to speak?

JH: Haha, I love that. And yes, totally, the website is an important part of the book. It was made by my friend, the brilliant artist Sam Lavigne. I love his work, and he was the only person who could have made this website, and I’m lucky that he agreed to do it. My publisher and I had a meeting with him, and our entire design directive was basically, “a shitload of cat gifs.”

In an early draft of the book, I had all the leaked NSA documents in the back as appendi-ces. They were cited by Motherfuck to corrob-orate what Rafael is talking about. But it made way more sense to have them exist online, in order to open up this other space for the book.

There were a couple ideas I had—that the book would come with an encrypted USB drive with all the documents, or that we’d dump them somewhere online behind a password, and the reader had to maybe solve some puzzles to get access. But I wanted to have more aesthetic control, so the website was the best way to go. Also, I mean, the concept is that this is Rafael’s website. It was super fun to imagine what that would look like. Like, he’s definitely not on social media, so what’s his homepage about? Definitely a lot of cat gifs.

GW: Rafeal is obsessed with flying, or at the very least floating off. Can you speak a little to the way this runs throughout the book, as maybe a metaphor?

JH: It’s not a metaphor.

gw: Fair enough. Perhaps an embodiment? I guess what I’m pointing to is gravity’s centrality in the narrative, not Rafael’s obsession with flying. I was looking at a previously published interview with Dan Bustillo, in which they speak of gravity in On Hell as a regime.

JH: I mean, in the text itself, his wanting to fly is not a metaphor. Rafael is literally hacking into his body to get it literally to fly.

It sounds like you’re asking what such an act points to, in terms of how it values the body, or what the body means when it is perceived as something to be physically transformed.

To answer that, I have to foreground that this is a crip book, and to come at the body from a crip perspective is always going to radi-cally redefine what the body is, not just onto-logically, but also physically, materially, and the primary way this will happen is to disin-tegrate the discrete-ness of it. And although metaphors can be useful here—I think of how figures like the monster and the cyborg are so generative in crip theory—crip-ness is also something that de-metaphors, or un-meta-phors, the body, and instead, insists that we deal with its actual, material, painful, sweating, fragile, needing, decaying, living being-ness. Like, what is a body without the cushion of metaphor? And in that space, what does trans-formation look like?

This is also what I mean when I talk about trying to get rid of the concept of ownership when we talk about bodies. In other words, it’s a reckoning with interdependency, how it feels and what it means to be so interdepen-dent, which is a much more accurate way to understand and think materiality than indi-viduality is.

I think the notion that our bodies are our own—both in terms of ownership again, but also that there is, or ought to be, a “real” or “authentic” self—is a neoliberal white-person fantasy. I always think of what Fred Moten told me about the etymology of “privilege” being the same as “private,” both of which come from the Latin privus, which just means individual. Privilege is simply being able to understand oneself in terms of one’s individ-uality, rather than how one is interdependent, formed in relationship, and deeply intertwined with systems of power, which is to say, inter-twined with sociality and politics. And to be private about oneself, if we think in Arendtian terms, is not to have to be political. For a lot of us, we are only ever seen through the systems of identity and sociality ascribed to us—our race, class, gender, disability, etc—rather than who we are as “individuals.”

So, it’s not a metaphor because Rafael can’t afford to be metaphorical. His body is literally the thing that is being incarcerated, though everyone pretends otherwise. He says, “to them I was totalmente nothing but a fucking symbol I wasn’t who I am they never saw me with two eyes and a sack of guts swimming in blood and pain and ambition and frus-trated exasperated dreamshit nah they saw me as brown and so quote unquote therefore.” It’s obvious to Rafael that to escape that, to find liberation, he’s going to have to start at the originary place of materiality that is untouched by metaphor. As he says, he must “hack that bitch to shit.”

GW: Can you tell us where Rafael is going?

JH: Lol fucking anywhere but here.